SPENCERTOWN, N.Y. IT was hard-edge paintings that made Ellsworth Kelly famous: large, geometric canvases full of smooth, pure color that make a striking impact on the white walls of museums and galleries everywhere.

“People looked at my work and said, ‘What are you doing,’ ” Mr. Kelly said over the summer, seated in his studio here in the Hudson Valley and recalling his early New York exhibitions at the Betty Parsons Gallery. “So I just stuck to my guns and worked at what I wanted.”

At 88, Mr. Kelly is again displaying his courtly stubbornness with the first museum show entirely devoted to his on-again, off-again series of wooden sculptures, at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (the show runs through March 4).

The warmly textured pieces on display, made from 1958 to 1996, show the softer side of the hard-edge master and complicate his formidable reputation as he is nears his 10th decade.

“This body of work has flown a little under the radar,” said Edward Saywell, the curator at the Boston museum who organized the 21-work show, which gathers about two-thirds of Mr. Kelly’s sculptures in wood. “But the way he distills form to its essentials, as in the rest of his art, is eagle-eyed and with a dazzling brevity of means.”

Ann Temkin, the chief curator of painting and sculpture at the Museum of Modern Art, said that the popular hierarchy among artistic media may be to blame for the sculptures’ relative obscurity.

“In general, sculpture is still such a second-class citizen for so many people,” said Ms. Temkin, who lent one of MoMA’s works for the exhibition. “It’s a knee-jerk reaction to think of Ellsworth and only think of his paintings — but that’s not an Ellsworth phenomenon, it’s us.”

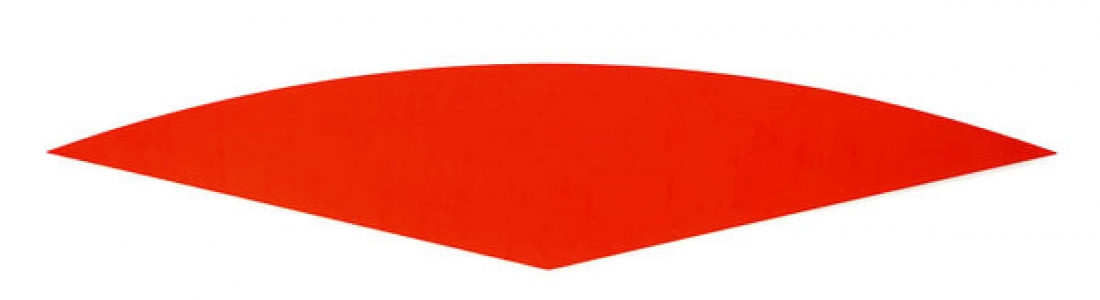

For “Curve XXI” (1978-80), one of the works in the exhibition, Mr. Kelly used the same wide fan shape that he turned into a signature over the years when working in paint. But unlike the uniform surfaces in the paintings, the all-over grain of the birch in “Curve” creates an elaborate visual pattern within the larger form.

“It’s Kelly, but with an accent,” said Malcolm Rogers, the director of the Museum of Fine Arts. “He lets the wood speak” — and, in so doing, pushes the viewer to comprehend his ideas about abstraction in a new way.

Mr. Kelly calls a number of tall, skinny works in the show “totems,” including “Curve XLII” (1984), made of zebra wood and featuring a distinct dark grain. The totems are easy to tip over, so the museum had to drill holes in its gallery floor to bolt them down and secure them.

That fragility is evidence of one of Mr. Kelly’s central ideas: what he has called the “still point,” or the balance that comes from two opposing forces. The forms may be inspired by Constantin Brancusi, whose influence Mr. Kelly has cited. He visited Brancusi in his studio in the late 1940s and saw versions of his “Bird in Space” and “Endless Column” there.

Though Mr. Kelly requires oxygen from a tank these days, he is still painting (though no longer in working in wood), and he moves among three tanks that are spread out across his large studio, designed by the architect Richard Gluckman. He lives in a nearby house on the same property.

In almost three hours of conversation, his energy level never flagged as he discussed the sculptures, to which he returned periodically over a 40-year period.

“The wood grain has taken hundreds of years to make,” Mr. Kelly said. “So the interest comes in the fast, modern cut of the shape set off against that.”

“Modern” is the word that Mr. Kelly uses as praise more than any other — right after uttering it he asked one of his assistants to look it up online, but didn’t wait for the definition to state what it means to him.

“Modern is contemporary — right now,” he said. “There’s no such thing as post-modern, because that is the future.”

The show in Boston is a homecoming of sorts. Mr. Kelly studied at the museum’s art school for two years when he got out of the Army in 1946.

“It was very conservative,” he recalled. “We all had to paint the nude in the round.”

His hunger for something new led him to Paris for six years, where Mr. Kelly looked at a lot of work by Picasso, among other greats, absorbing his mastery of line and composition. In one crucial way he defined himself against the master: “I said, ‘Picasso’s work is too personal for me. I only want to paint form and shape.’ ” He came to believe that stripped down and pared-back works were more potent vessels to carry what Mr. Saywell called “flashes of remembered visual experiences.”

One of Mr. Kelly’s first works in wood, “Form in Relief,” came in 1958. Mr. Kelly saw the depth created by stacking the two relief panels — and by the space between the relief and the wall — as another way to elaborate on his ideas about form. It gives a sense of the echoes and progressions found in nature, which have always been a keystone of his art.

“I said somewhere that I like the rock and its shadow,” he said. Indeed, the Museum of Fine Arts’ installation creates dramatic shadows on the walls behind each work.

From the beginning, Mr. Kelly declined to treat the material with stain or varnish. “When do you do something to it, that’s furniture,” he said.

The wood grain also provided a new way for Mr. Kelly to explore the intersection of the act of drawing — which he considers the basis of all of his art — and the surrealist penchant for lucky accidents.

“I like the idea of chance,” Mr. Kelly said, citing the babylike shape that can be seen emerging from the grain of one of the totems in the show.

Mr. Saywell said, “The wood grain is almost a found drawing in these pieces, a magical form of calligraphy.” Still, though he has embraced chance in some of his art, Mr. Kelly’s career has been the product of firm intentions from the beginning.

“I think a lot of people have said, ‘Oh, my kid can do that,’ ” he said with a chuckle, referring to the results of his strictly minimal approach. But he believes that it is precisely this approach that keeps his work from looking dated.

“When you look at a Warhol of Jackie O., 10 or 20 years from now it will mean something else because of the subject matter,” Mr. Kelly said. “I like to think that some of my work at least will stay in the present tense.”