By Ciarán Bennett

‘To make something beautiful; you have to be somewhere.

The Rhode Island Red cock,

he stood on the white wall

and called for the day the cloud

filtered light, faded towards the

mountain from the distant drumlins.

The stillness was punctuated by the

long line of shrill Blackbirds and Robins,

a rainbows on curved air, echoed

in the silence

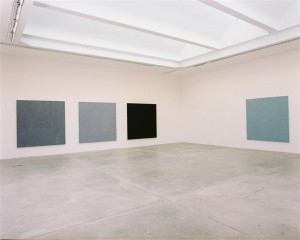

Iron Mountain in a home, a studio, an inhabited place. The mountain temple of Doi Sitep in northern Thailand, a square structure with four walls of bells above the cloud line, where the constant chant sometimes pierces the mist of the valleys leading to china, is for me a powerful metaphor for this place. The meditative silence of the large muted paintings sings of the simple geometry of such spaces. The unison of high light, a luminous grey pink, which shades the mountain view, has found a physical presence in the fragile pattern of stone and reflected serrated galvanised roofs. The tonal intensity of these linear grids finds a visual articulation in an inch square reality of a small brush mark, within the predetermined ischrony of a painted square. Its longitude and latitude a precise math, its density a grey tinted blue orange mark.

The shadows and light bring an image to mind for which there is no initial inspiration, but the painted-one inch grid system itself. The under colours show as negative pattern when the weft and weave is occasionally loosened within the formal freedom of a constructed space, they are a painting from within, I call these lyrical, as they are immediately open to see as pattern and image, but somehow they are less accessible within themselves as marks. Lyrical Ballads did not make the understanding of the poet’s meaning or experience any easier, yet in Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Xanadu, Kubla Khan and rivers of enchantment are an internal dialogue, of a fractured construct. And in this context, maybe the open trellis pattern of some of these works finds a structured formalism, and it is actually more of a journey to its real identity, than the appearance. This development from tight weave to open loose verticals is leading the eye beyond the surface, and exploring the dynamics of the sublimated colour. This allows the viewer to read the appearance of a visual narrative; the shapes are open within a concise interlocking motif. The starting point of exploration takes a greater involvement, when the surface discourages an obvious visual illusion. Yet the dialectic of paint has its own resonance. It is questioned and examined as material here, by exploring the opened painted interior framework. The blue and red big squared flag works of a few years back were leading to these small one-inch grids. The sequence is there the muted synthesis of an oyster shell, mother of pearl grey in the dawn, yet luminescent in the shade.

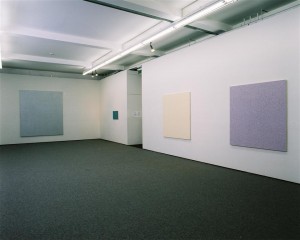

Looking again at the work which I first saw in Drumshanbo studio, and painted in that well-proportioned room then returned to the intense light of the mountain. The surface qualities of Drumshanbo have been eviscerated, and up here the clear lines of their construction are as linear as the singular ash trees in winter. This winter observation had denuded the leaves, the surface impressions of continuity, to reveal the trellis of their construction. The yellow of fragile cowslips with the undertow of buttercups, is not warm now, it is as if the theoretical dictums of hot and cold are mute, and here only the vibration of the frequency harmonise. The sound quality is always so impressive; the rhythm of John McGahern’s prose is lifted by occasional thrilling crescendos. The ever present bird song are intersecting lines of ash and thorn. They become a delicate weave, a spider’s web constructed of mist and sound.

The painted construction of a predominately abstract mode of art making, mathematical in its inception often invokes the occasional glimpse of rectangular geometric associations. Denis mentioned that while painting a large rectangular painting in and around 9/11 the two vertical sections he had started left and right, appeared as the two towers, these thoughts are not necessarily so oblique. These works do have an affinity with the process of the constructed parallelograms of urban high rises, which are essentially a grid of steel frames with poured or applies concrete. These urban associations, the night light of thousands of small rooms across the horizon of any major city, are always redolent of Manhattan, particularly the island view from Brooklyn at Williamsburg. Denis worked and lived there in Williamsburg, the home to a variegated art making culture. For me the rooftop views of Manhattan have always been so spectacular across the East River, particularly at night. This pointless grid of domestic light, made from walls of small stamp-like windows, squares of muted and shaded light, are a mosaic of human existence, characterised by the simple arithmetical unity of their construction. There is an innate visual sympathy between these manmade boxes for habitation with their fixed patternage of apertures to the light, and the constructed severity of measuring a one inch grid on a six-by-six foot canvas. The engineering qualities of such measurements have a basic affinity and constructed physical three-dimensional reality. Yet it is the illuminated patternage of such physical constructs that give them such transcendental sensibility, particularly when seen as a wall of tiny electric squares of light, a pattern designed by the physicality of their construction.

The arithmetical construct is also found in nature, with ephemeral tracings of accumulated romance and artistic association. Bird song as Klee’s pedagogical linear markings, dissect this landscape of tree lines and flat pewter plates of distant lakes; the rising undulating hills towards the south enclose the mountain and exclude the plain from the vision of this place. There is a panorama of misty encroaching landscape, with its well tended – often symmetrical – fields, yet always the delineation of distance is the bird songs scything presence, in winter cold and clear, yet misty to the horizon, the tits and finches dissect the landscape with their calls. The radio was on the studio ‘some ghost is out there’ the spirit of George Campbell maybe; his late abstractions evoke the same landscape.

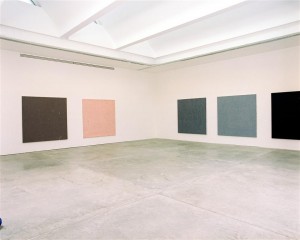

The hedge that marks the first line of the horizon from both the studio and the house is fuschia; it articulates the mist of the distant drumlins and lakes. Its presence, even now as stakes of dead bush, maintains the hued splendour of its definitive frequency of purple red, tipped with stamens of pink and yellow white. The painting entitled Fuschia Mist Dawn, explores the colour field of muslin that wraps the landscape, the mist enraptured drumlins need a key to unravel their encroaching presence. The mountain is an island surrounded by lakes and delineated fields of patchwork construction, the fuschia is the solid colour key to the muted ash banks, and the shady green of their leaves.

Dandelions, buttercups and birdsfoot, are patterned, shaded by reeds, they are the local bamboo, and they transect everything here. It is almost impossible to consider the surface of the land without these arbiters of vertical pattern, the veil or screen to see through have fuschia and Pissaro’s pinky blues at dawn, with the intersections through the trellis of trees, bare in winter yet potent now with sap.

The organic sensibilities of these paintings have translated the minimalist nature of many contemporary exploration of the grid, into a symphonic gesture of human existence. The often coldly arithmetic construct of reinforced urban experience has led to an equally arid resolution to this form of art making. The work of Sol Le Wit concerns itself with such minimalist gestures, but even here, the recent cube series, somehow manifests humanity, lacking in the larger museum pieces, mostly worked on by assistants. This individual human gesture, within the constructs of such simple geometry, has an affinity with its sources in Archimedes and the ancient Greek magic of measurement. These abstract imaginative ramblings are central to the Cabla and the Hermetic understanding of the essence of nature. It is within this understanding of geometry, as means of exploration, rather than construction, that these painting these paintings operate as icons of nature. The often confused denigration of romanticism, as some rather trite sensibility, also denies the fact that Greenberg considered the abstract expressionist school of New York, as the last romantic modernists. If we consider romanticism as a search for a natural understanding of existence, within the metaphor of the poetic imagination, then we are approaching the sensibilities of this work. The isolation of the place wherein the work was made gives these paintings an element of meditative rapture, within a landscape of often startling simplicity. That these paintings are visions of place, does not obviously equate them with the often trite understanding of the concept. They are abstract moments of sensual painterly absorption, incorporating both the male and female natures of the painter’s evocation of place.

Ciarán Bennett

Dublin 2003.