By Robert C. Morgan

These are not paintings made for everyone nor are they paintings that anyone can do. They have a specific point of view. They offer a perspective on the process of painting itself. The process not only a material concern, but one that relates to structure, surface, incident, and colour. In essence, these are paintings that allude to the phenomenon by which we perceive meaning. Their tactile surfaces embody time, and, in this sense, they represent the subtle process of signifying.

I have often been heard heralding the dictum that to paint suggests a heightened degree of knowledge about the act of painting. To possess knowledge in relation to pigment presupposes something about the way art signifies. This is good and well enough. But what is ultimately more important is the artist’s willingness to relinquish all of all that one knows, that is, to unknow everything that stands in the in the way of painting. This decision happens withholding any doubt that he or she is fully capable of doing exactly what needs to be done.

Few observers involved in today’s corporate-driven, globalised environment would accept such a dictum. For many, art has vanished from the spectrum of intelligence. Only (authoritarian) space and (pragmatic) time remain. But such a paradigm takes us back to the Euclidean era when space and time were held as separate entities. Without a relevant link between them, there is little realization of experience or, for that matter, of history. Yet for those who have spent significant time working in the wilderness of material existence, the challenge to relinquish all that one believes to be the case remains omnipresent. This is the point where art becomes an inevitable direction towards fulfilment, in other words a consecration of meaning.

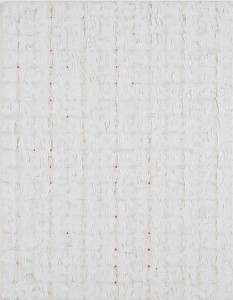

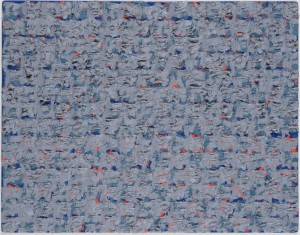

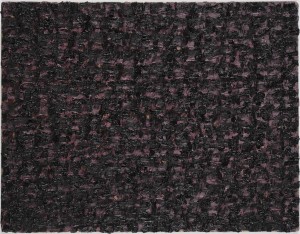

Based on what I have seen, the painter Denis Farrell appears to be such an artist. To make these densely overlaid white surface happen, to give them a life and vitality than does not succumb to pretence or sudden inhibitions or distortions of belief, is an extraordinary feat. Farrell’s vivid colour resonates through a hidden language that is visibly read behind every mark, behind every module where pigment is applied. For Farrell, painting simply is, but is rarely simple. The grid is the uniform support that gives immediate closure to the brushwork. He doesn’t fuss over rows of numbers or suffer delusions of becoming monkish. Rather he paints the grid as a means towards dissolving it, thus giving the substratum an equal tension and balance that few will properly understand. Farrell’s colour is of essence. He needs the support of something uniform in order to make the colour function, to give it the proper solitude of expression, that is, to make colour signify an idea beyond the normative status of the broken sign, the empty symbol, or the formalist cipher.

I have seen works by some of the Japanese and Korean Mono-Ha painters of the sixties whose work followed a similar path as the one set forth by Farrell. I believe their commonality is the result of a cultural cross-current, an ecology of mind, more in the manner of affinity than influence of each painting as space is created through the assessment of light both within and against the surface. Le Corbusier found a similar result in architecture, but never in painting. Here I refer to the magnificent wall created on the leeward side of his Church in Ronchamp where parishioners experience an interior cave-like impression. As with the Mono-Ha painters and the late architecture of Le Corbusier, Farrell’s commitment to the structure of art is also close to nature and equal to the landscape that drenches the soil and air around his Irish homestead. It would be difficult to imagine how such paintings could exist independently of nature or without the mind that forms itself within the relativist time/space construct of nature’s perpetuity.

To write about Farrell, as least for the distant mind that works the keys of the electronic pulse behind these signs, is no less a task on honing in on evidence of what one sees. As I have often realized in painting, to know is also to feel. The starkness of Farrell’s application of paint, the repetition of the stroke, the single-handed endeavour of standing perpendicular to the obdurate surface in line sight, is something beyond comprehension. There is little one can say of the raison d’être behind such activity. What exactly is he making? In our corporate age of indulgences, overwrought with glamour and variations on exhausted themes, what sense does a painting by Farrell hope to make?

In abstract terms, Farrell’s paintings are both there and not there. No one can guarantee the communication of anything that strives to be significant, because real communication always involves a certain depth, a synthetic layering of meaning. The risk is enormous, and beyond belief. As I look at photographs of the walls of Farrell’s atelier and compare one hue with another, as I absorb the density and complexity of these retinal effects, the optical journeys that entice the mind’s eye as deeply as the soaked soil around him. I hold in suspension the idea that Denis Farrell can never know exactly where a painting is going to go. Large or small in scale, Farrell’s surfaces remain consistent. There is a certain terror in holding the nest of a bird, and so it is. Farrell’s painting is like holding the nest of a bird.

At a New York after opening dinner party last week, I was asked to give a short talk on the work of one of the exhibiting artists. I began with an intensely terse inhalation of ontological gibberish presumably destined to articulate the artist’s simulationist position. At one moment a voice emerged from a table in the rear, somewhere in the shadows of the ristorante. The voice was intent on challenging my claims; “Can you be more specific?” Happily, my Zorro-like retort was in fine fettle that evening: “For you, I can only be more general.” This laid the pretentious ruffian flat. From then on, I was able to make my case on aesthetic and critical grounds. When I speak of art, apart from the promotional rhetoric expected by today’s investors, I often conflate the specific with the general in a manner to avoid theorizing upon what is unnecessary to say. I am looking for a complete access to the work, a vision that I sense intuitively that somehow runs parallel to the often hidden intentions of the artist.

Indeed, it is a conundrum to speak or to write on an artist’s work from a perspective that tries to address the interior motivation of something that appears in the surface. But in the case of Farrell’s paintings – to see how cadmium orange red and cadmium red medium both contribute to the density of the painting’s proclivity toward optical absorption- is to resist isolating what is specific about them from what is generally the case. The semiotic intrigue of his colour bears down upon me in a midst of sensing their overflow. All the while, the tactile resonance of these intimate surfaces keeps my eye steady in the centre of the force-field, signalling solitude without fear of recompense. No equivocation resides in my desire to experience the depth of his surfaces. These paintings are about intimacy, offering a subtle potion against an encroaching standardization that pressures artists to bend to the trends of globalization. With Farrell, the force-field is secure. There will be no giving-in.

Robert C. Morgan

2005

Robert C. Morgan is an art historian, artist, curator, lecturer, poet, and art critic, who has written extensively on modernist and contemporary art and on issues of globalization and culture. He is author of Art into ideas: Essays on Conceptual Art, Between Modernism and Conceptual Art, and The end of the Art World and is the editor of books on artists Gary Hill and Bruce Nauman and, most recently, on the late writings of Clement Greenberg. Morgan teaches at the School of Visual Arts and at Pratt Institute, both in New York City, and was the 1993 recipient of the Arcale award for art criticism presented in Salamanca, Spain. He lives in New York City.