By John Yau

Weekend Studio Visit: Denis Farrell in Oughterard, County Galway, Connemara, Ireland

Hyperallergic Weekend – August 24, 2014

The first work by the Irish artist, Denis Farrell, that I saw was in New York. It was a box titled Ukiyo (2011), containing seventy equally-sized, abstract watercolors. Ideally, the watercolors are supposed to be framed and mounted across all the walls of a gallery, becoming a sequence inviting the viewer to look at each work.

The first work by the Irish artist, Denis Farrell, that I saw was in New York. It was a box titled Ukiyo (2011), containing seventy equally-sized, abstract watercolors. Ideally, the watercolors are supposed to be framed and mounted across all the walls of a gallery, becoming a sequence inviting the viewer to look at each work.

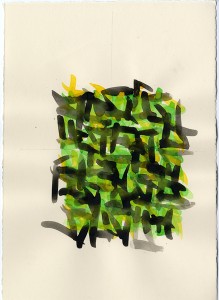

For each painting, he used a ruler to divide the paper into equally sized quadrants, drawing a vertical and horizontal pencil line that intersected at the surface’s center. In each of the four spaces he made a four-stroke configuration of watercolor, which hovered between a tic-tac-toe game and a loosely painted square. Rigor and variation, control and dissipation, overlapped. I was intrigued and began asking questions.

According to the artist, he started working within a set of guidelines in 2001, when he became dissatisfied with his work, and gridded off an eight-by-eight foot painting that he had been working on into one-inch squares. As he put it, he wanted to find a way to get across the surface. He used a number one short, flat brush, filling the entire grid by making four strokes to restate each penciled square. By repeating the same non-expressive strokes in tandem with the penciled grid, Farrell was able to mark time as well as shape his passage through it.

Denis Farrell, from “Marcantonio Brangadino’s Envelope” (2010)

Literally translated, Ukiyo means “Pictures of the floating world,” which conveys the sense that nothing is permanent, that everything is passing away. While the word is associated with the woodcut prints depicting the pleasure-seeking aspects of Japanese urban life made during the Edo period (1600-1867), in the West it has also come to mean the depiction of everyday life by such renowned artists as Hokusai (1752-1815) and Hiroshige (1798-1858). Their prints of ordinary people and the landscape influenced the Impressionists in terms of composition, color and subject matter.

Farrell’s title, however, goes back to the awareness that Ukiyo is a homophone with the Japanese term for “Sorrowful World,” which is how Buddhists describe the never-ending cycle of rebirth, life, suffering, death, and rebirth from which they try to escape. By marking time with a brush full of watercolor–whose density of pigment ranges from thick to thin–Farrell’s works belong to that company of artists that includes Roman Opalka, On Kawara and Peter Dreher. The difference is that Farrell does not count (Opalka), does not date (Kawara), nor does he depict the same water glass again and again (Dreher). Younger than this generation, all of whom were born in the early 1930s, and were undoubtedly affected by the horrors of World War II, Farrell shares something with the reductive impulses that are central to Minimalist artists such as Robert Ryman, Brice Marden and, to a lesser degree the Radical Painting of Marcia Hafif. What distinguishes Farrell’s work from these American painters is the connection he makes between making and time passing, which seems to be of little interest to them.

It is his consciousness of time passing, of art as a repeated act, combined with an intense material sensitivity, and, in the watercolors, a sensitivity to color and light that spans the spectrum between materiality and immateriality, that sets Farrell’s work apart from these two generations of older artists. I brought up Ryman while looking at a painting with a creamy white impasto surface punctuated by pimple-like protrusions scattered almost evenly across the surface, to which he responded, “Sometimes I wander into someone else’s garden and have to find my way out.”

This observation conveys Farrell’s innate faith in the process he has devised for himself, secure in the knowledge that by moving across the surface something unexpected will happen, leading him into an unanticipated direction

The other thing that struck me while sitting in the front room of his two room studio in Oughtergard, looking through his boxed groups of watercolors, with titles such as Letters to My Father ( 2014), Poems to My Father (2013-14) and Marcantonio Brangadino’s Envelope (2010), is the extent to which consciousness of time, fragility and persistence underlie all of his work. Letters to My Father and Poems to My Father were done shortly after the artist’s father died, while Marcantonio Brangadino’s Envelope refers to the Venetian Captain-General who led the defense of Famagusta in Cypress against the Ottomans. Fighting a vastly superior army, he was able to resist inevitable defeat far longer than anyone expected. Shortly after surrendering in July 1571, and negotiating what he thought would be a peaceful transition, Brangadino was mutilated by the Turkish commander and then flayed alive. His skin was stuffed with straw and sewn shut, and his body, dressed in military garb, was made to ride an ox through the city. Some art historians believe this horrific event inspired Titian to paint the Flaying of Marsyas (1570-76).

Denis Farrell, from “Poems to My Father” (2013-14)

Willem de Kooning famously said: “Flesh was the reason oil paint was invented.” Is it far-fetched to suggest that Farrell is making a connection between the thin layers of watercolor and skin, underscoring its transparency and wetness? I know I had a visceral response looking at the watercolors – I literally felt a shiver over my body. While it was impossible not to connect the red strokes with blood, or to think of the brush as a kind of knife, these connections occurred in my mind’s eye, no literal image was needed.

At the same time, there is something beautiful about the light radiating from the depths of Farrell’s layered watercolors, the insistence that they are daubs hovering between the physical and the impermanent. Finally, there is the self-consciousness of looking, of going from one watercolor to the next, and the sense of how fleeting time is. I become aware of my body sitting in a chair in a small room of a gray concrete house with a red door on the outskirts of a village in Ireland, the light streaming in through the window, and how none of this will last.